My Legion Year

On reading every (pre-Zero Hour) issue of Legion of Super-Heroes - and what the characters were and could be

Jim Shooter died.

I should preface all this by saying I did not know Jim personally - we emailed maybe a handful of times, for interviews while I was writing for Newsarama (and perhaps Wizard), and - most notably to me - when I was helping coordinate a Dave Cockrum industry memorial in New York during my first tenure at DC, circa 2007.

I reached out to him about attending and was glad he could make it. It struck me as one of the few times so many heads of Marvel and DC were in the same room - Kahn, Levitz, DiDio, Harras, Shooter, DeFalco, Quesada, Carlin, to name a few. Anyway, I didn’t know him well. I knew of him, sure. I’d read many interviews - particularly those Wizard ones during Valiant’s heyday, and later more historical appreciations of his time at Marvel (which was contentious and controversial). I remember enjoying his blog, too, when it was active. A clear peek through the curtains of an industry I had yet to become a real part of. But I didn’t know him. All that said, I didn’t expect to feel like I got to know him a little better this year, through the Legion of Super-Heroes.

It started simply enough - I wanted to find something to read to my kids. We read a lot of comics before bed. The stuff that seems to resonate the most with them are stories from the Silver Age. We’d hit a dry spell, though. We’d done early Spider-Man, some 50s Batman, a bit of 70s Claremont X-Men, and a smattering of Lee/Kirby Fantastic Four and some Silver Age Avengers. My son, 9, was game for all of it - and had already started reading those huge ESSENTIAL X-MEN black and white phonebooks on his own (we stopped right before the Mutant Massacre, don’t worry). But I needed something that appealed to him, but also drew in my younger daughter, now 6. I needed to find something that evoked the period - for content reasons, but also because they seemed to entertain - but also kept them engaged. I landed on The Legion of Super-Heroes.

(In an earlier post, I talked about my personal experience with the Legion, through the prism of a bigger essay on the “everyone’s comic is someone’s first” idea, and how it’s a little flawed when taken literally.)

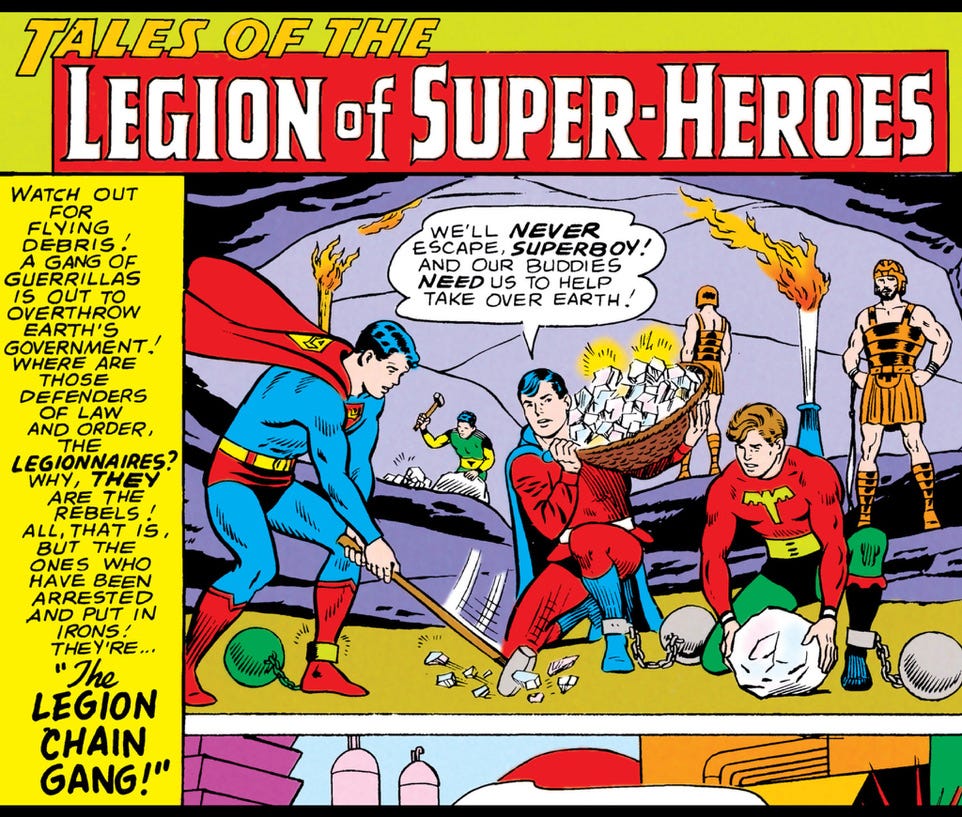

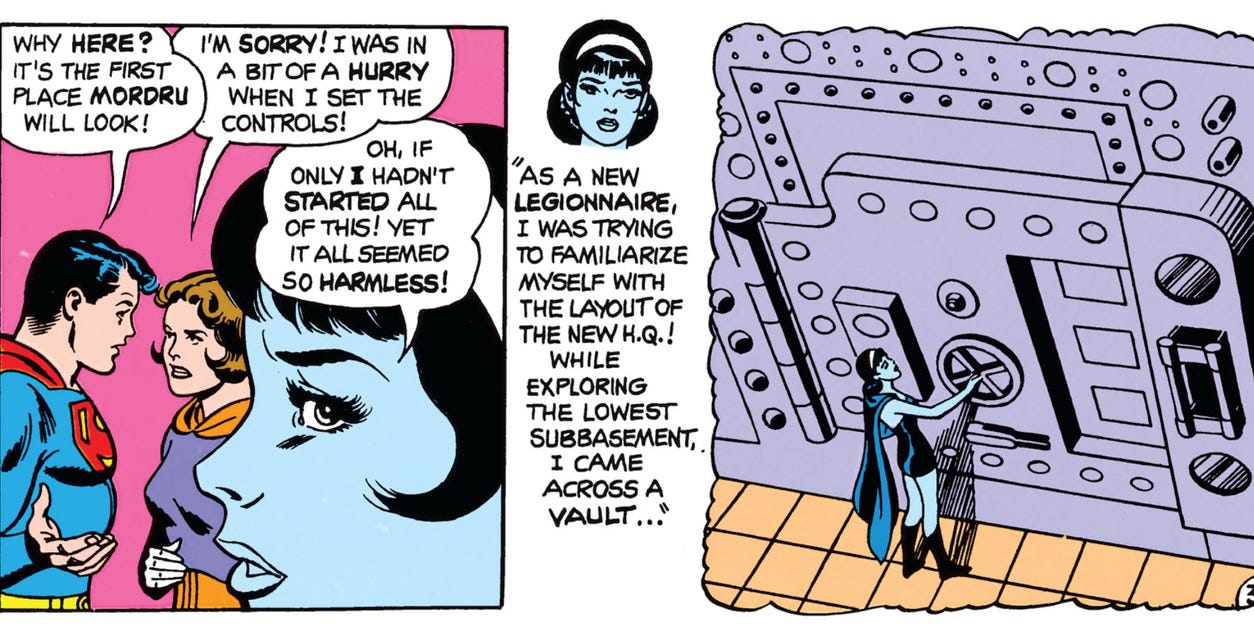

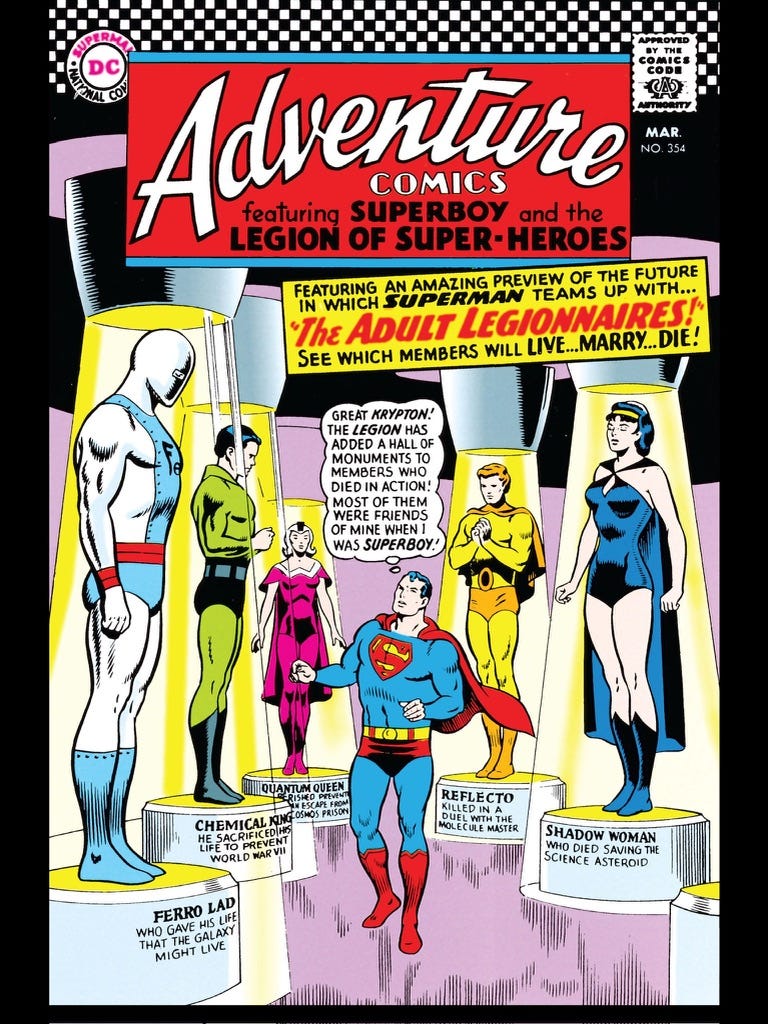

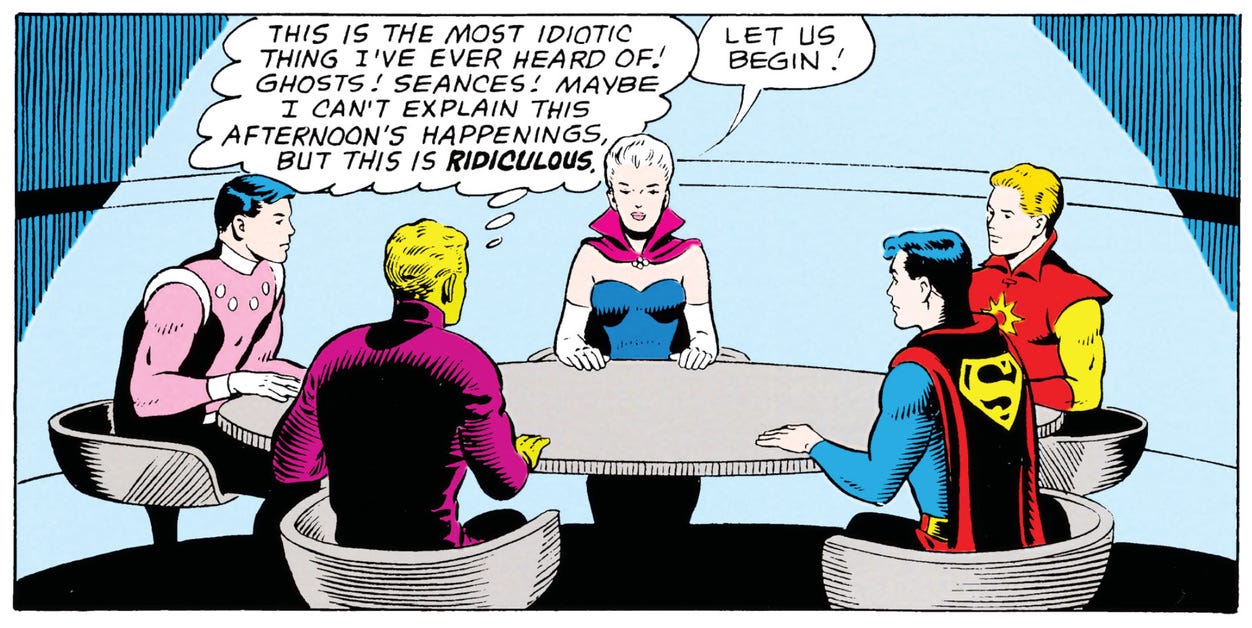

It was the perfect choice. But it really didn’t start to cook for the kids until we got to the Shooter era – where he seemed to collect the threads and random ideas the likes of Hamilton and Bridwell had tossed out and gave them cohesion. But it isn’t just the perfunctory – Shooter gave the stories a verve and spark that was missing from contemporary DC titles that felt a bit rigid and stodgy (except for maybe Doom Patrol). Whether it was villains – like the Fatal Five, Mordru, Universo – or characters – like Karate Kid, Princess Projectra, Nemesis Kid – or concepts like the Sun-Eater, the Shooter Legion felt fun and lively. Shooter knew how to write plots that kept readers rapt – whether it was introducing new members, having a traitor in the team’s midst, killing a Legionnaire, or peeking at the future of all our favorite teens, his stories – especially when drawn by the legendary Curt Swan – felt timeless and energetic, but still loaded with stakes and peril. A comic written for a general audience that still managed to entertain at every level. Easier said than done. This wasn’t a niche document that riffed on continuity – these stories established the lore that writers decades later would still be riffing on themselves, and did it with confidence and flair, in a way only an actual teenager could. Shooter’s Legion had a childlike wonder that was missing from most other comics out there. It was no surprise, then, to find out Shooter (at age THIRTEEN) had been a DC fan who discovered Marvel and noticed that very difference – and pitched stories writing DC characters in the style of Stan Lee and his artistic co-creators.

The stories of Shooter taking the train from Pennsylvania and sneaking into his editor’s Manhattan office to turn in his scripts have been told many times, so I’ll spare you, but I do believe that it was that childlike energy that worked its way through time and into my kids’ brains as we read those stories together. They loved the bright colors, the silly code names, the fantastical plots, time travel, and the idea that the future was a better place because these teenagers had figured it out. It felt good. Even when characters died or were hurt (poor Luornu), the team came together and powered through.

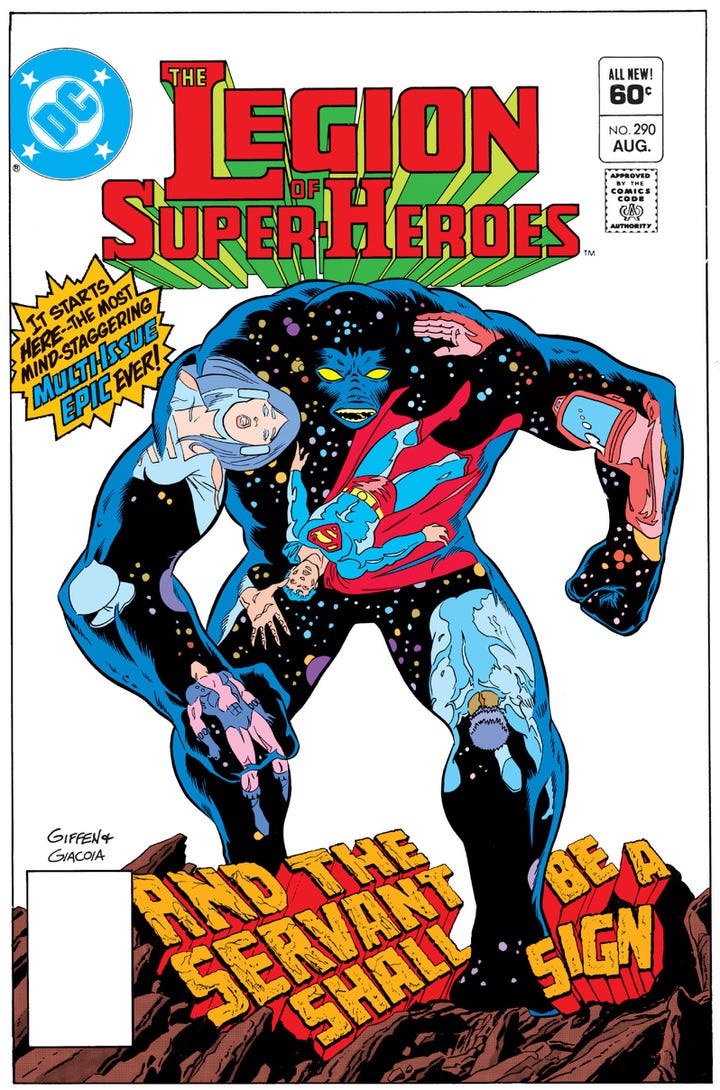

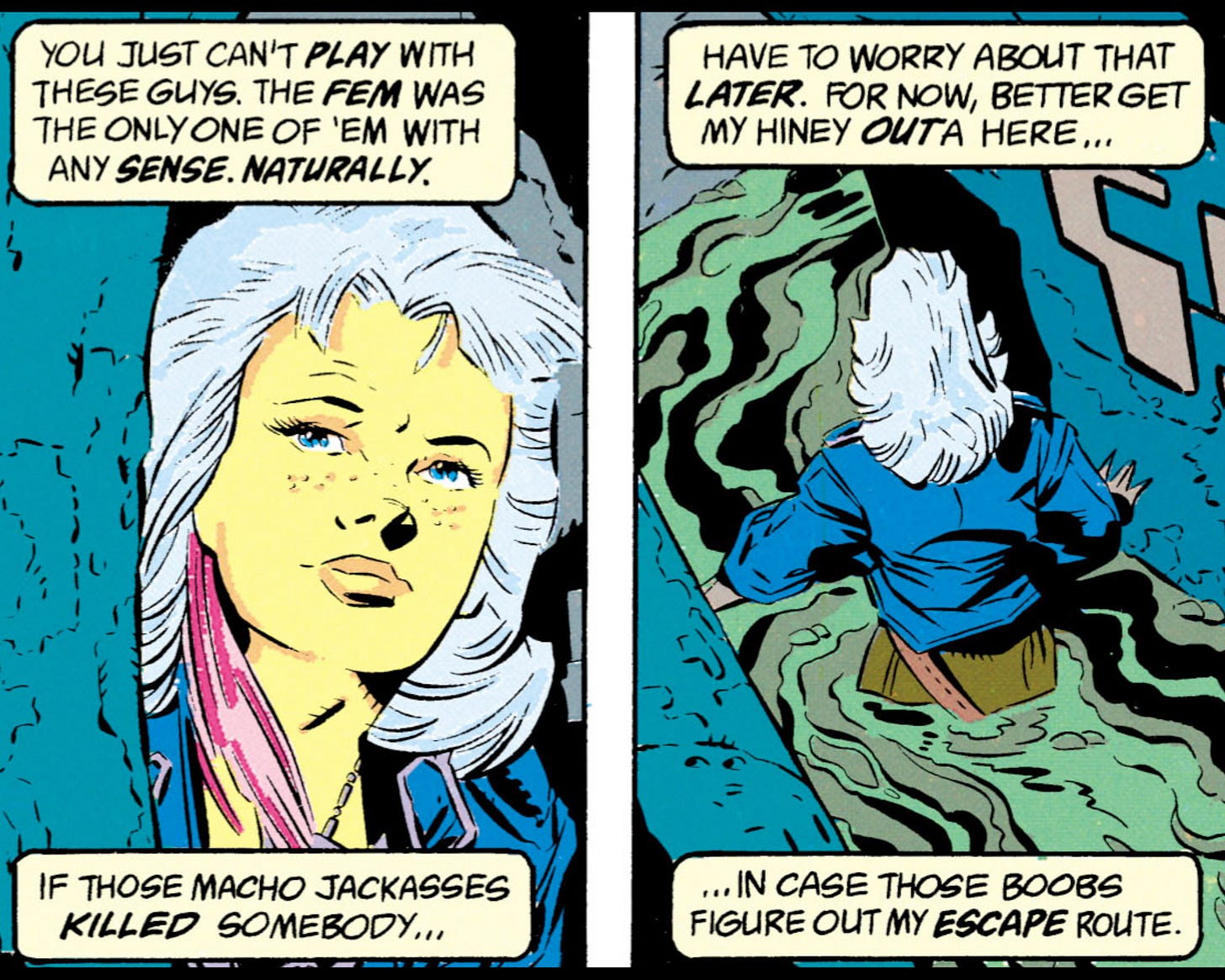

Thus began part of what I now call My Legion Year – which still seems to be ongoing. While I was reading the Shooter run to the kids, I was hungry for more – for something to read on my own time. I thought about diving into the Levitz/Giffen run, but something pulled me in another direction. On paper, it made no sense (it still doesn’t). But for some twisted reason, I thought I’d start reading with Giffen and co.’s Five Year Later storyline, which jumps from Levitz and Giffen’s finale ahead, uh, five years to tell a story of a fragmented and lost Legion, and the desperate efforts to pull them back together. (Sidebar: for those that label 5YL a big departure from what came before, I’d suggest they revisit the last few arcs of the Baxter run, by Levitz and Giffen, which is loaded with stylistic nods toward what’s to come - especially visually. Giffen even uses the grid! Anyway…)

Like I said in my earlier post, this run is not what you’d traditionally call “new reader friendly.” The heroes rarely use codenames, they are sparing in their exposition and recap, Giffen (at least when he was drawing the book) adheres very passionately to a nine-panel grid throughout, and…the Legion doesn’t exist. There are data pages! It’s a grim look at a book that was, in its earliest incarnations, a bright and cheery journey through the future through the eyes of wide-eyed and optimistic teen heroes. I won’t re-litigate the debate my last post sparked, but suffice to say – it was the perfect, immersive experience for me at the moment, as someone who had a passing understanding of the Legion but didn’t have the love for the Legion. Not yet.

But as I searched and read about these characters as I encountered them in the pages of the Giffen saga – “Who is Rond Vidar?” “Why is Shvaughn Erin important?” “What the hell is a Takron-Galtos?” – I started to piece together the mythos, and I felt transported back to an earlier time, to an age when I didn’t have a laptop at my disposal, or Wikipedia - when I had to basically serve as a detective, collecting tidbits of information about characters and comics to understand the greater story – when a stack of trading cards, a few issues of Comics Buyer’s Guide, and a few rec.arts.whatever posts would have to set me up enough to understand what was going in. It was kind of exhilarating.

And it was an unexpectedly great way to prepare for reading the rest. That’s right – after finishing Giffen’s run – and then watching the line collapse under the temporal weight of Zero Hour, which basically erased all vestiges of the original Legion (a task even Crisis on Infinite Earths and subsequent retcons couldn’t fully accomplish despite editorial fiat’s best efforts) – I went back to the beginning, picking up post-Shooter and starting with Cary Bates and Dave Cockrum’s take on the heroes. And I just kept going.

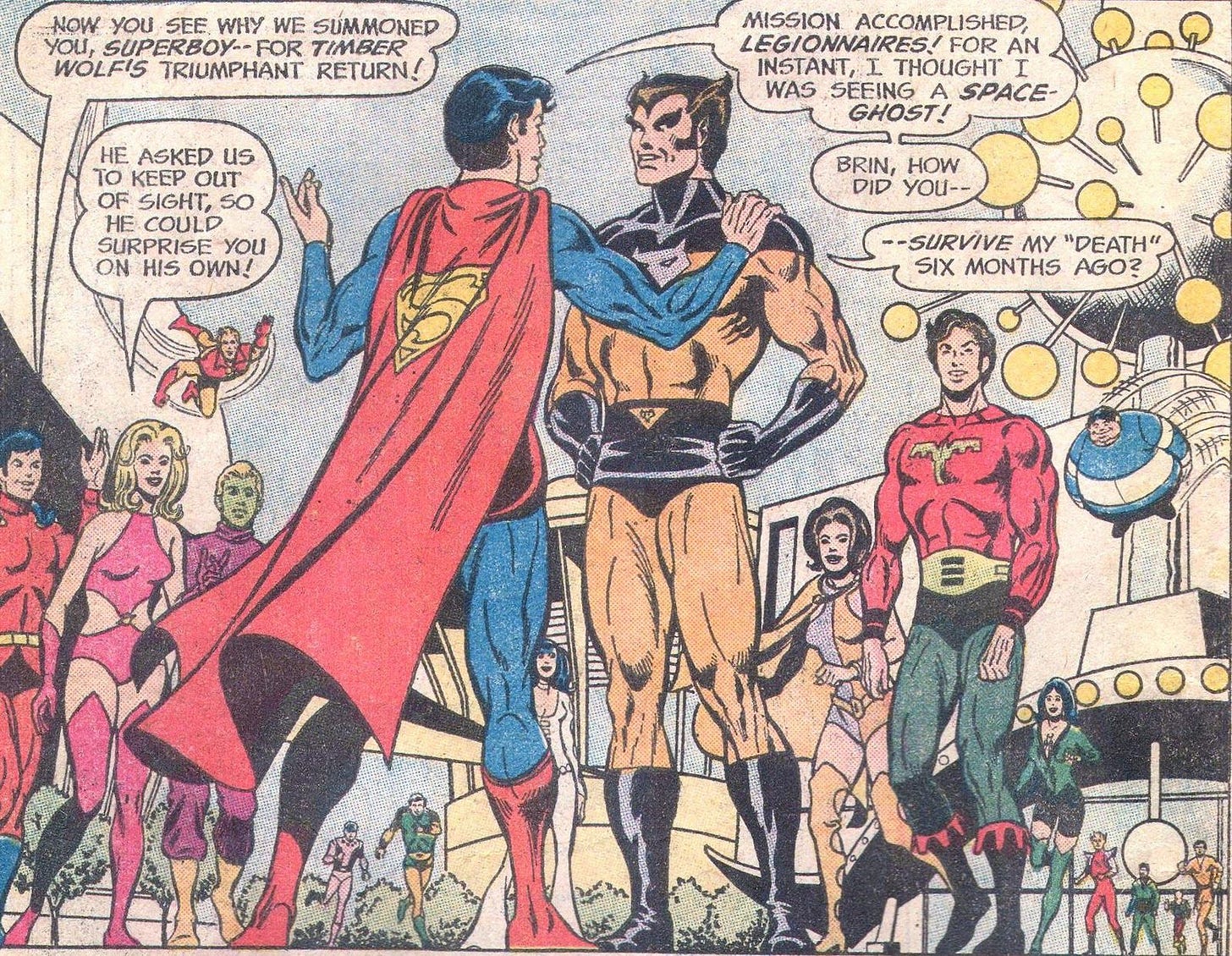

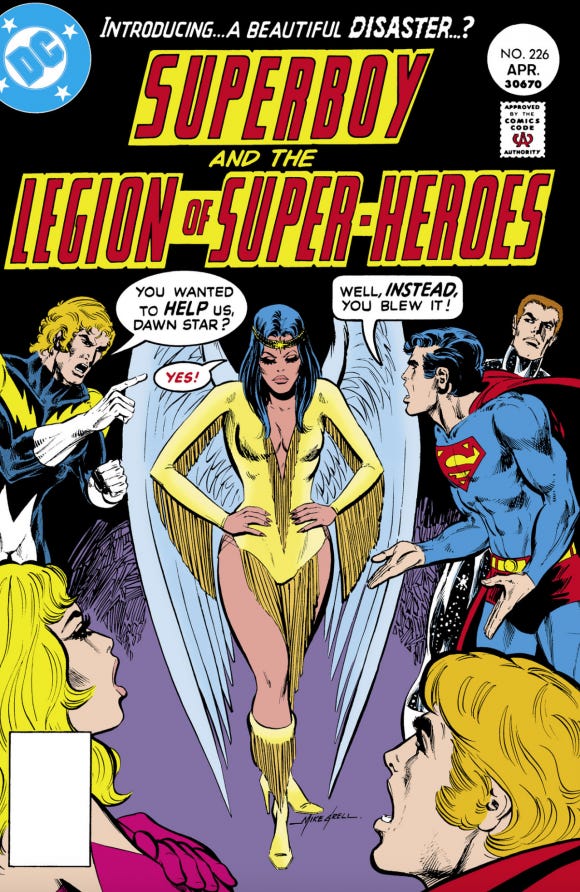

I marveled (no pun intended) at the stylistic power of Cockrum – and how he visually reimagined these Silver Age teens and basically prepped them for the Bronze Age, elevating Bates’s sturdy, episodic plots and giving the team a modern look and feel. Rokk, Imra, and their colleagues were no longer “oh golly”-esque teens, but sexy, college-age heroes facing external and internal conflicts that added dimensions to their character. When Cockrum left, the baton was passed to folks like Mike Grell, Mike Nasser, and more - this was a more realistic, hard sci-fi Legion. Beautiful people from all over the galaxy who all looked different and fought hard. It was no wonder Cockrum would go on to bring many of his ideas and all of his passion to the rebirth of another iconic franchise - the X-Men. But like I said, the stories still felt like they were ripped from the Silver Age. Competent craft, at times engaging, but something was missing.

They needed a soul.

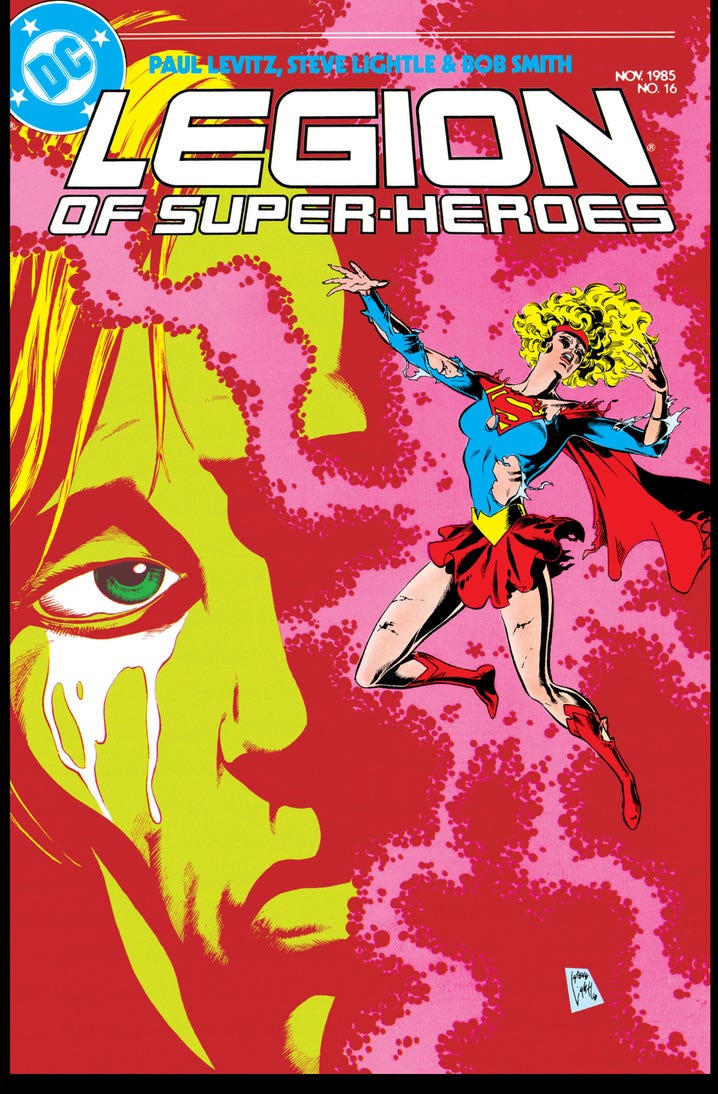

Enter Paul Levitz.

As I noted last time, I’d read bits and pieces of Paul’s run - most notably The Great Darkness Saga. But like the first time I read 5YL, it was without context and understanding. This time, I had the wind at my back. I got to experience Paul Levitz’s career-defining run on LOSH at hyper speed – from the shaky/hesitant beginnings of his first era (which started when he was 20!) to the powerhouse finish of Earth War, illustrated masterfully by the woefully underrated Jim Sherman and capably completed by veteran Joe Staton. You could see where Levitz was going, and even reading these issues now, with no wait between them, I felt a pang of regret that he’d left the series, and even felt nostalgic when Paul came back for a lovely holiday one-off with the king, Jose Luis Garcia-Lopez. I wanted to keep reading this guy’s take - because he seemed to have a handle on the characters that I couldn’t find elsewhere.

He cared about them, it felt like, and that’s rare. I sped along through Conway and Thomas’s at times entertaining and always solid runs – but clearly runs done as gigs in the wake of the DC Implosion, which even Paul attests to. The work was done, and done capably, but it lacked the passion and obsession that I felt crackling off the page when I read even a middling Levitz story. A friend, Margot Waldman (who wrote a must-read piece on the Legion here), likened the Levitz run to episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation - even the “middling” episodes were fun because the characters were great and you care for them. I find this to be a really apt comparison.

With Levitz’s Legion, even the lesser work was of a certain quality, and provided a needed comfort when reading. You wanted to spend time with these characters, who all felt different and alive. It’s hard to achieve that - to be able to keep the level of content up so high that even your doubles and triples drive in runs. So, if Cockrum, with all his genius, visualized the modern Legion, Levitz breathed life into them - he made them whole.

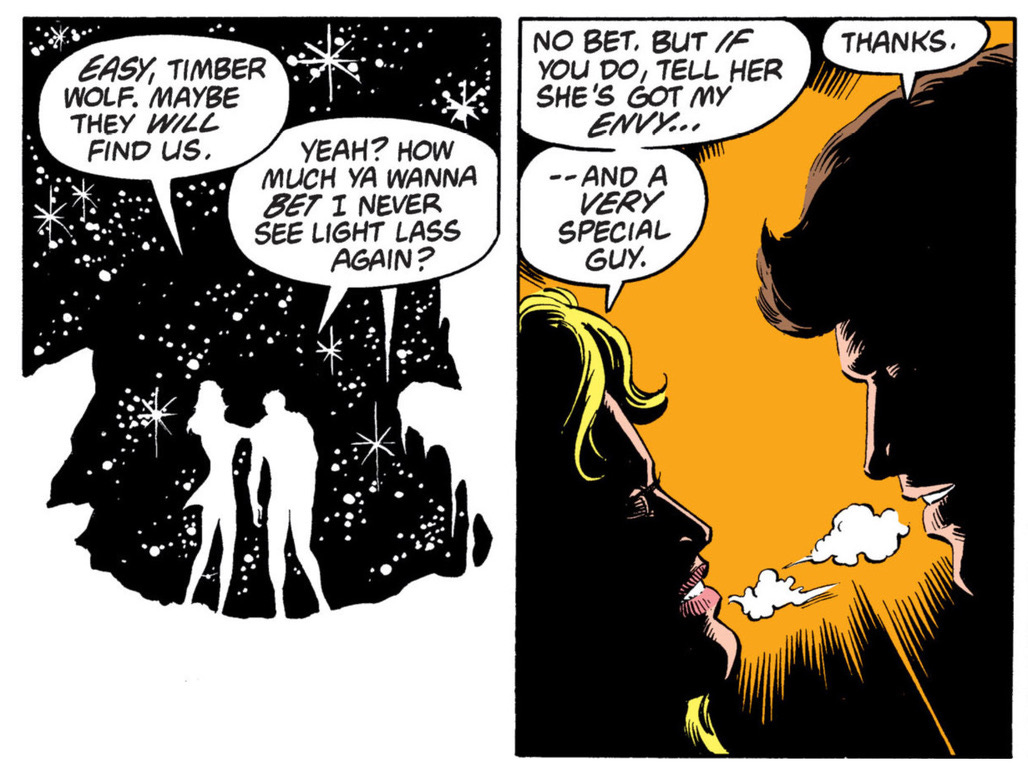

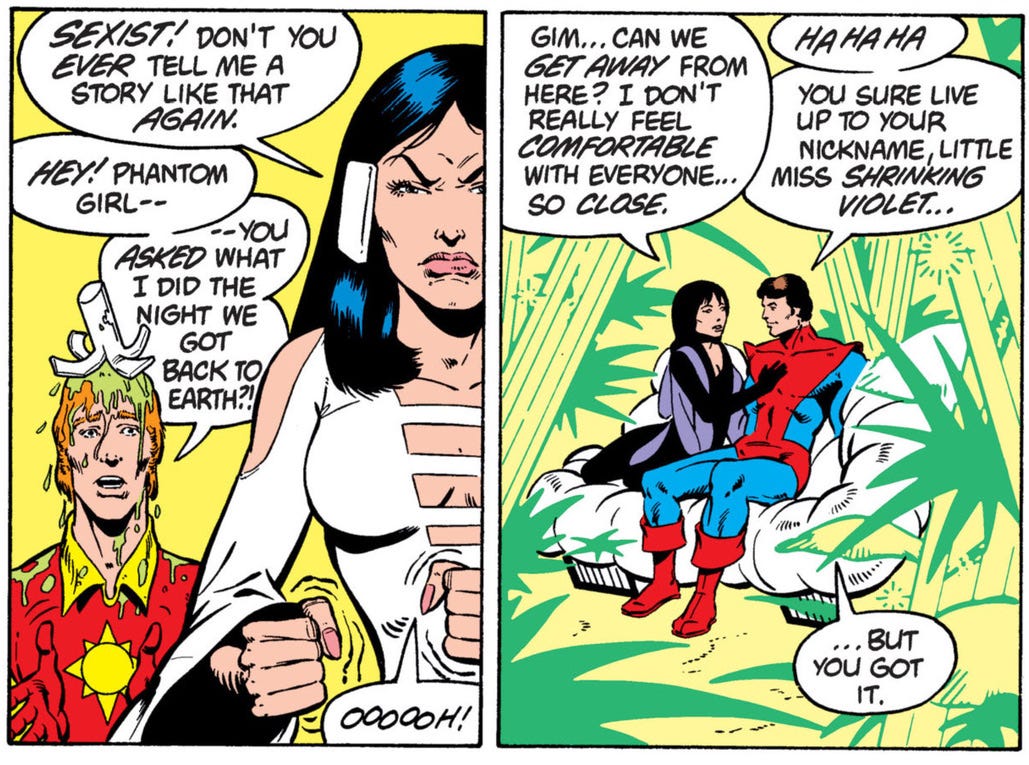

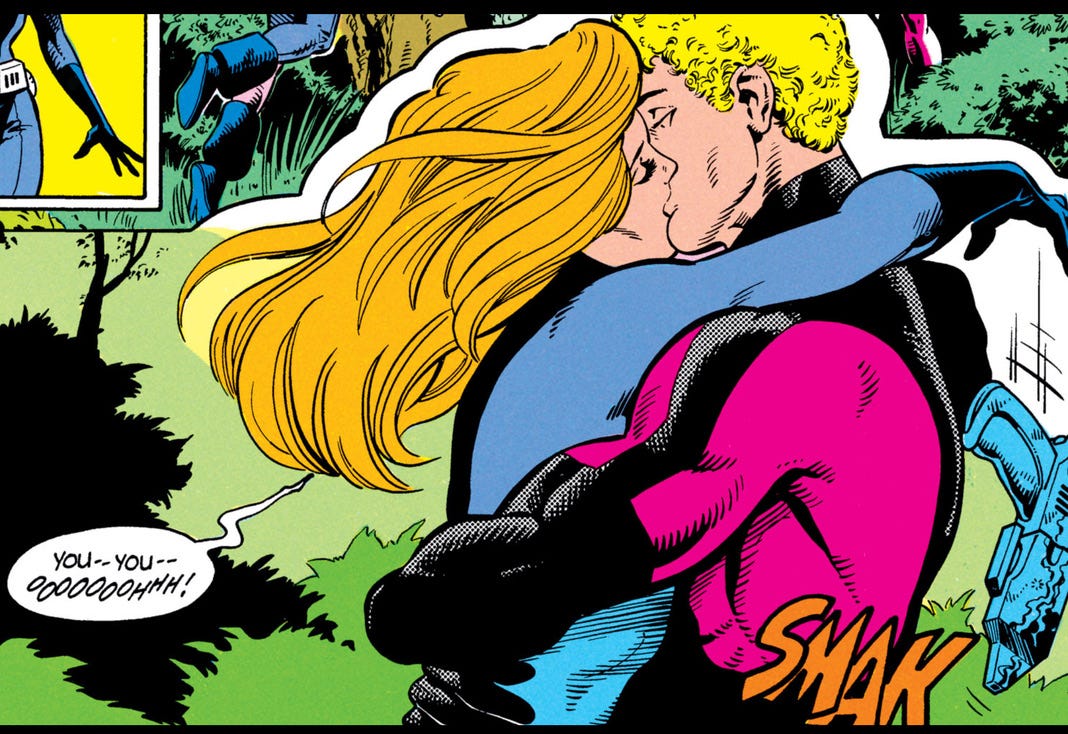

They were no longer Smurf-like heroes that were defined by their powers but talked the same (no offense to Shooter, but it was always more about the plot with his stories, and less about the pathos). Levitz gave each of the characters a voice and a point of view – whether it was Dawnstar’s ego, Wildfire’s thick-headedness, Rokk’s calm, Brainy’s distance, Blok’s kindness, or Nura’s sultry insight – each hero felt like a unique person, even dating back to Levitz’s earliest stories. The adventures were less about the villains (though Levitz had a knack for building up to a big battle - as Great Darkness Saga, The Universo Project, and Magic Wars each attest) and more about how these young, smart, attractive heroes played off each other. So when Paul returns, first with veteran artist Pat Broderick and then with Giffen, it hits like a roundhouse kick to the face. All the pieces have clicked together.

The Levitz we see here, building toward the Great Darkness Saga, is confident and comfortable - and it brings me to one of my biggest compliments for Levitz, the writer. The man can plot. In comics, it’s very much a lost art form these days, with few series lasting past five or ten issues, but there was an era where in mainstream superhero comics, you as a writer could seed a plot and then play it out almost a year later. Some writers were particularly good at this - like Claremont, Mantlo, and, of course, Levitz. Denny O’Neil talks about it in detail in his sadly out-of-print The DC Guide to Writing Comics - dubbing it “The Levitz Paradigm.” You should really try to snag a copy of this book if you can find one - my copy is worn out from use. But basically, the Levitz Paradigm was the structure/format Levitz used when working on a long-running series, specifically Legion - the idea that you start with an “A” or main plot, but carve out pages and space for “B” and “C” plots that will, eventually be elevated to “A” level, all while introducing new supporting plots. It sounds overly technical, but as a writer who also prides himself on craft and structure in an effort to compete with folks who I think have more natural talent, I found this process extremely relatable creatively, and the results spoke for themselves.

If, say, Chris Claremont’s X-Men run was more about general directions fueled by vibes, the Levitz/Giffen/Lightle/LaRoque/Giffen “Baxter run” was precision machinery - fleshed out characters having friction and working toward a common goal. The stories felt lived-in and complicated. Not only were the Legionnaires people - they were messy. Messy professionally, messy romantically, and messy in life. In interviews, Levitz often jokes about deciding which character to torture, but that makes for great fiction, and his love for the lore - as seen in various Silver Age flashback issues, and one-offs drawn by Legion veterans (most notably Curt Swan, who continued to be at the top of his game well into the 1980s) - combined with his deep understanding of who these people were, made for one of the most immersive and often progressive superhero sagas of the era. Need a concrete example? Check out Levitz and LaRoque’s long-simmering Sensor Girl saga in the Baxter series. Levitz masterfully drops clues about the new Legionnaire’s idenity to create a fun “B” plot that eventually crashes onto the main stage. When Sensor Girl’s identity is revealed, you’re either surprised and upset because the clues were all there, or you feel validated because you figured it out based on the clues. The elements of a great, strategic mystery.

I’m a big X-Men head, specifically Claremont, and it was interesting to read the Legion with that in mind - as these runs were happening pretty much contemporaries, and there are a lot of interesting parallels between the Levitz Legion and Claremont’s X-Men (and, to a lesser degree, the Wolfman run on Titans). I think that’s an essay unto itself, but generally speaking, these two runs are very much in conversation with each other - if not intentionally, then subconsciously. What Claremont seems to do instinctively, Levitz does methodically in terms of character developments and plot twists, but the end results feel very much cut from the same cloth - teams of complicated, messy people pushed to the brink and dealing with the consequences of their action. That just sounds like DRAMA, right? But I choose these two runs because both do that drama very well - the soap opera that is integral to great superhero comics is on full display in both runs. People like to read about heroes making mistakes and overcoming their trauma or complications to do the right thing - and sometimes the right thing creates another set of issues. The challenge of longform, novelistic superhero writing in a shared universe is truly fascinating, and these two masters really show you how it’s done.

My plans for rereading Five Years Later are not comprehensive. I figure I’ll read the Giffen run for as long as it feels fun, and then I’ll figure out where to go next. My gut tells me to head back to the Levitz era, via Geoff Johns and George Perez’s epic Legion of Three Worlds mini-series, and then see how far I can get with the modern Levitz work. I’m also intrigued about revisiting the Mark Waid/Barry Kitson “Threeboot,” too. But reaching the finale of the main Levitz run felt like a meaningful ending point - and, in closing, a chance to look at the Legion as a whole. I’d also suggest reading Margot’s fantastic, two-part Legion retrospective again. It is very much running parallel to a lot of what I’ve been writing here.

It’s not a reach to say the Legion has been rebooted and reimagined a number of times, and folks often point to this as the reason for the challenges the property faces. I’m sure every reboot was well intentioned - like DC as a whole in the 80s, the lore of the Legion was probably seen by many as too arcane and complex to welcome new readers. It’s a strong argument to say a clean slate was needed. I was on staff at DC when Mark Waid and Barry Kitson relaunched the Legion, which thematically gets closest to what I think would work today (more on that below) and I was also around when Geoff Johns and George Perez “retrobooted” the characters back to their pre-Crisis/Levitz era, as part of Final Crisis. Both started with genuine excitement and energy, and were consistently good in terms of quality - but both suffered fates all too common to the marketplace at either time. Does that mean there’s no place for the Legion today?

For me, the most intense part of Margot’s essay was this sense of emptiness - that the Legion she loved was now forgotten, a relic of a time long past. It’d be terribly sad if that were the case, though based on my reading of the industry news, it doesn’t seem to be. And it makes sense. From a business perspective, the Legion is too important a franchise for DC to leave dormant forever. The question becomes, then, what to do with the team? I should preface this by saying I have no real insight into what’s happening with the characters now, I’m just riffing. I’m sure whatever is coming is in great hands and I’ll be first in line to read it. Based on what little I’ve seen, color me intrigued.

All that said, I’m happy to flick two pennies into the fountain and share my thoughts, for whatever they’re worth (perhaps less than two cents).

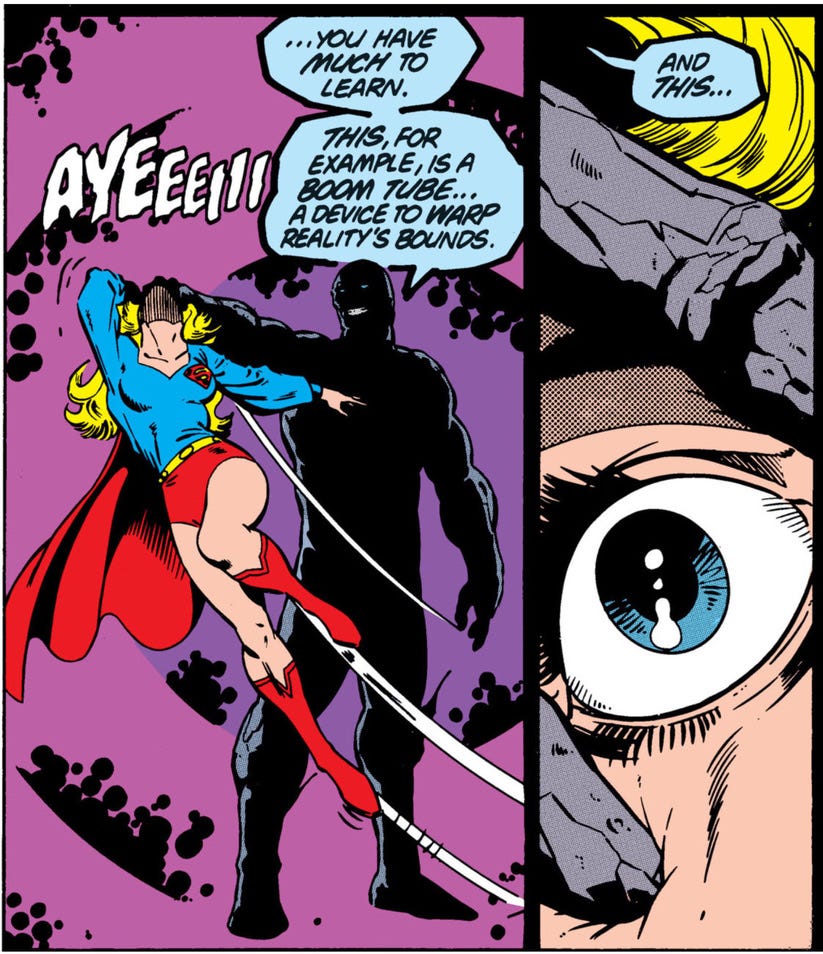

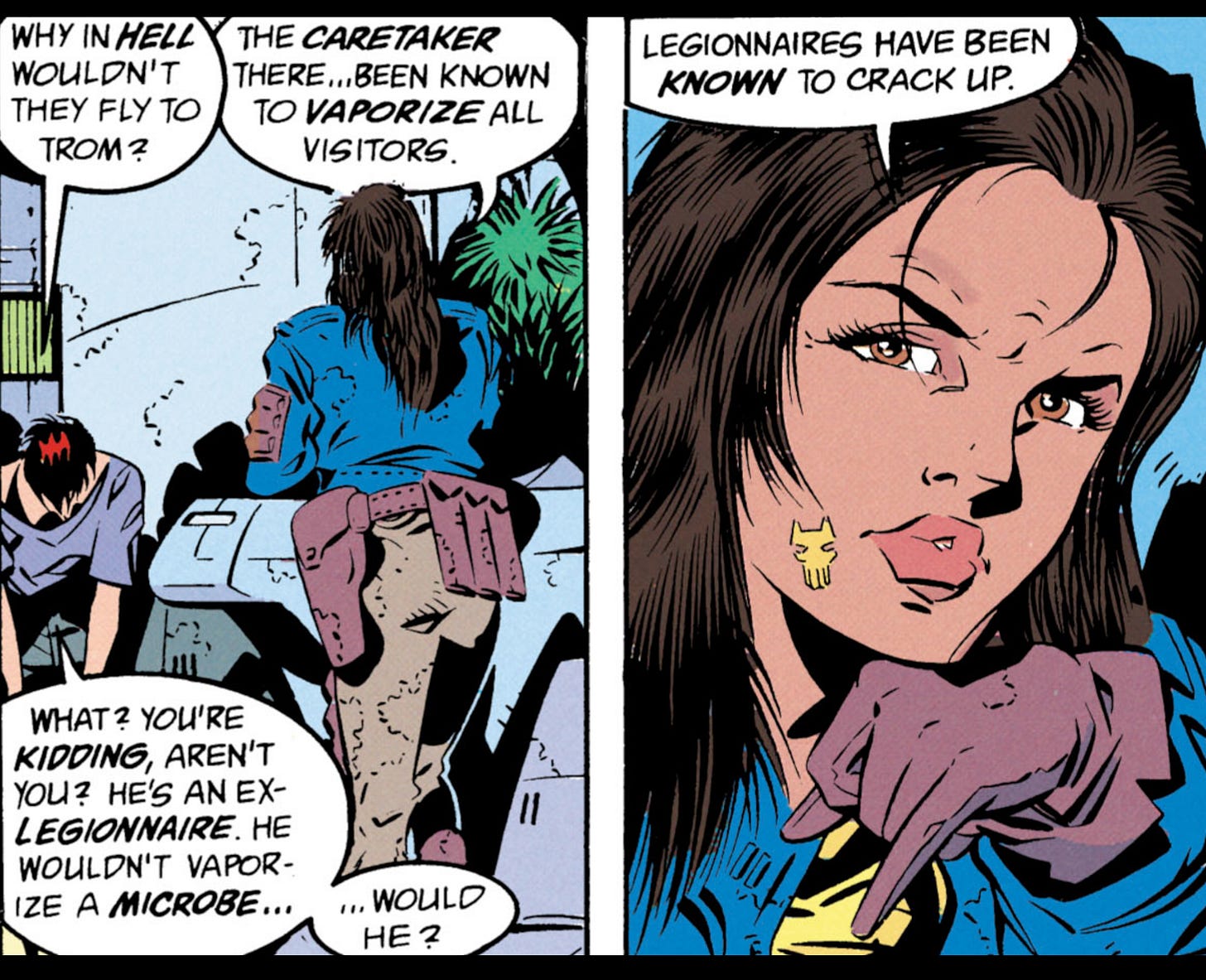

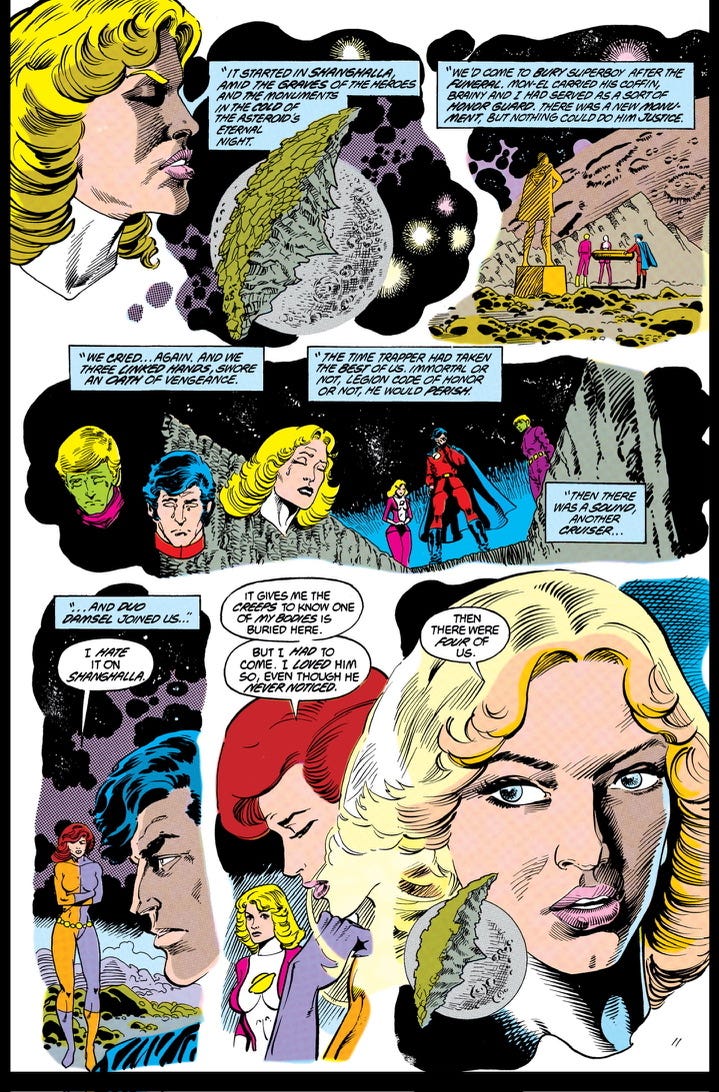

Lukewarm take: I think, by and large, the series lost its anchor with the erasure of Superboy during the first Crisis. John Byrne’s decision to have Superman start his heroic career as an adult, while clean in terms of his Superman narrative, inadvertently negated decades of his beloved adventures as the Boy of Steel, and therefore undercut the core idea of the Legion - that this group of future teens was inspired by the greatest to ever do it, Superman - before he was even an adult. Levitz’s fix - that the Superboy the Legion knew and loved was actually the creation of the Time Trapper via a pocket universe for nefarious purposes - was smart and made sense, but couldn’t overcome the idea that the Legion, as we knew it, had been inspired by and befriended a “fake” Superboy. That, coupled with the later editorial mandate (Byrne was long gone by this point) early in the Giffen 5YL run, that the book could no longer reference even that “pocket Superboy,” or the team’s shared history with him and the also-retconned away Kara Zor-El Supergirl, was a stumbling block that began that iteration of the Legion’s long, slow demise, ending with Zero Hour and a complete reboot. I say long and slow because Giffen, along with Tom and Mary Bierbaum and editor Mark Waid (he pops up a lot in the story of the Legion!), came up with a genius solution all things considered: instead of Superboy, the Legion, via the death of the Time Trapper, had actually been inspired by…Valor.

Wait.

Who the hell is Valor?

Good question. Valor is Mon-El, or Lar Gand, a key member of the Legion and, as some of you recall, a character that first appeared in the Silver Age in Action Comics. His powers and look are almost identical to Superboy, and like Clark Kent, Mon-El has a deadly weakness to lead in lieu of Kryptonite.

His origins and lore are tied to Superboy, but not inextricably - a native of the planet Daxam, Lar Gand landed on Earth amnesiac, and was dubbed “Mon-El” by Superboy - who believed him to be his lost brother. And it was Monday. The Silver Age was fun. Anyway, reeling from the editorial edict but still facing a deadline to get an issue out, Giffen and the Bierbaums decided the cleanest solution would be to have Mon-El stand in as Superboy in all these old stories - which, in theory, makes sense. They’re similarly powered, they’re in most Legion adventures together, it tracks. So, if you squint, you can kind of see it. It also opened the door for the introduction of Laurel Gand, a new character and cousin to Lar who would stand in for Supergirl (and, in my opinion, work better than Supergirl), who as most of you know, died in the original Crisis and was also written out of Legion lore. Now, you just had to pretend those old comics you had featured Valor and Laurel Gand, not Superboy and Supergirl. Easy, right?

In the short term, yes. There’s a genuine, vibrant excitement to the first dozen or so Five Years Later issues - spurred by a fluidity of story that was part and parcel for Giffen, but also a byproduct of the rules changing as the game was played. I hate the euphemism “we’re building the plane mid-flight,” but it felt very relevant here. But it brings me back to my greater point - the Legion works because it’s the future of what we know. The Superboy connection is the throughline. We’re seeing a young Superman learn the lessons that will inform our present in his past and our shared future. We see elements from the classic DCU in the future in a different way - Levitz plays with this a bit, particularly with Rond Vidar’s final form and more, and Giffen (and his collaborators) tie things together more tightly with L.E.G.I.O.N. It’s where the TNG comparison comes in again. I loved the characters and the stories, but the connective tissue to the greater Star Trek universe locked me in. Seeing Doctor McCoy in “Encounter at Farpoint,” or Spock in “Reunification” felt important and special, and it amplified this already-great sci-fi story by tying it into a bigger lore.

It felt like those stories counted, and when the Legion future felt connected to the DC present, I had the same feeling. This is where the books were heading. Recent reboots have recognized this - Waid does a great job integrating Supergirl into the Threeboot Legion, Bendis’s take includes Jonathan Kent Superman, and Johns reestablished the Superboy/Legion connection in his Superman and the Legion of Super-Heroes story with Gary Frank. It’s not the be-all, end-all solution by any means (what is?!), but I don’t think it’s a coincidence that when the DC present was disconnected from the pre-Zero Hour Legion via retcons, general interest in the LOSH waned. In an extreme way, some of the stories just felt like Elseworlds - a possible future that might happen but you don’t have to worry about, to paraphrase Cerebro. The stories have to feel like they matter.

Tonally, one of the takes on the team that I felt really worked was the Threeboot era, where Waid and Kitson treated the teens as rebels - defiant, powerful, and fighting for the oppressed. It felt like such a cool, fresh take on the concept, and it was simple and clear - these cult heroes/kids are the resistance. It also solved the clunkiness of the “teen space cop” conceit you’d have to deal with today. Make them punk kids, not police officers. I need to revisit the Threeboot soon, so I can’t comment on the execution beyond the issues I read while working at DC, but I remember really enjoying that run at the time - and the idea to tap into the youth of the team, vs the continuity.

And speaking of continuity - I don’t think folks are wrong to feel daunted by Legion lore. I certainly was. It took me years to come around to reading the series, and even then I chose to dive into the deep end rather than the beginning. “Might as well learn as I go,” was my thought. Oftentimes, this leads to rebooting or relaunching the concept, starting fresh so readers can get in on the ground floor. As I’ve said before, I don’t think this always works. You lose something vital by wiping everything away. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that some of the most successful books of late have been takes that evoke the past (“retro adjacent”?) but feature modern storytelling sensibilities. Readers are smart, and they’re interested in compelling characters and conflicts more than sussing out where in the canon a story happens.

Most importantly, and going back to the X-Men parallel, I think there’s a diverse, queer, progressive, and young part of Legion fandom that’s really looking for new takes on the characters that evoke the books the readers enjoyed - so it’s actually a perfect time for the characters to return.

The Legion, like the X-Men, has often been about people from all over coming together to fight for the greater good. Though not necessarily outcasts like the X-Men, the Legion, to me, always felt like a welcoming place for all - and that’s important.

No matter what, I’m intrigued to see where things go. After this year, I’m more invested in the future than ever before.

Long live the Legion.

What a great piece, Alex. For some reason, the ADVENTURE-era Legion books were the first back issues I started collecting as a kid, probably due to being fascinated by the sprawling cast and deep history.

Thanks for taking the time to put this together.

the Legion Lost “era” of Abnett & Lanning (2001-2004, Legion Lost, Legion World, and then 33 issues…) to ME, was the (as of this date) closest Legion-esque series since the Levitz/Giffen runs. Not to be overlooked - but this team exits in Final Crisis …. then the Waid/Kitson run happened in ‘04